FINDING MY WAY TOGETHER WITH YOU: A Teacher’s Guide to supporting non-native students through strength-based learning (includes sharable materials)

I. Introduction to Strength-Based Learning

This Guide was prepared by the Faculty of Education and Teacher Training at the University College Leuven (UCLL) as an introduction to and support for strength-based learning in the classroom. Strength-based learning can be used for all students, but this Guide was created especially with students from a migrant, refugee or newcomer background in mind.

While the traditional approach to learning focuses on setting standards for students to reach, in doing so, it often zeros in on a particular student’s weaknesses in meeting those standards. The student has ‘deficits’ and needs to find a way have to make up for them. In focusing on what a student lacks, many traditional approaches forget that particular school system standards are often culturally determined. That is, there is an emphasis on what a student can’t do within a culturally determined framework of expectations instead of what he or she can do. This doesn’t mean that learning standards are forgotten or erased. On the contrary! Standards are kept, but the goal of achieving those standards might be more easily achieved when students realize that they are valued for who they are and what they can already do. In a system that incorporates strength-based learning to their standards, students are encouraged and realize that they have the agency and freedom to achieve those standards, but also are given the socio-cultural and emotional tools to do so.

Students from refugee, newcomer and migrant backgrounds, who have left their own culturally determined framework of standards, might fall through the cracks in the new one, if they are constantly being told that they ‘lack’ something. As human beings, we all know what it feels like to be overlooked, ignored or misunderstood. Research shows that when a student too often hears that he or she is ‘not good enough’, they begin to lose hope and too easily give up trying. They might look for other paths to fulfil their dreams than school, leading to various forms of (self)-destructive behaviour and delinquency. Focussing on a student’s deficits within the context of a particular system doesn’t sufficiently take into account what a student might have already learned in another system or through experiences in his or her family and community. It also fails to take into account his or her particular talents and gifts, which also need to be developed.

In 1996, Jacques Delors’ report to UNESCO, International Commission on Education for the 21st Century, encouraged educators to support students in finding pathways to develop their “treasure within”. Although committed educators believe that this is the goal of education, often teachers have neither the skills nor the right tools to do this. Strength-based learning is something of a Copernican revolution in teaching and learning in that both the teacher and the learner are given tools that help the teacher help students and the students to help themselves in taking responsibility for their learning processes. Hence, we have developed a Guide with basic tools for both teachers and students to integrate strength-based learning in their classrooms and their lives. Throughout this Guide, teachers are provided with the tools that they can easily download as MS Word or Excel documents to use in their classroom and or share with their students.

In the second section of this Guide, Finding My Way Together with You, we provide both the theory and research behind strength-based learning. We explain why taking a positive instead of deficit approach to learning processes is important for working with students from a refugee and migrant background – in fact, regardless of their background. We pay special attention to the OICO-principle (Observation, Imitation, Creation and Originality) as a foundation of strength-based teaching and learning processes.

Strength-based learning is highly aware that the context of learning is as important as the objectives or standards of learning; hence, in the third section, we discuss the contexts of learning in terms of time, space and personal connections.

There is no magic pill that solves all problems. Sometimes teachers are at a loss when things go wrong and what they can do to restore order and a positive classroom climate. In the fourth section we provide both a strategy and tools to cope with the challenges and hurdles that can arise in a classroom. Strength-based learning draws upon the knowledge gained from research into bullying (whole school approach) and restorative justice, seeing the classroom as an entire socio-ecological system (Bronfenbrenner). Before a solution can be devised, a tool is given to help map out the relationships in the classroom. Teachers then follow a flexible 8-step strategy that supports students in creating themselves a more positive classroom climate.

The fifth and sixth sections concern the mapping of students’ strengths and employing these in the lessons. Teachers might then begin to ask the question: how can I tell whether this is working? Hence, the seventh section provides a framework and tools to evaluate the student’s progress, but also for the students to evaluate their teachers. Teachers are free to use (or not use) the teacher evaluation tool should they feel comfortable with this more democratic and revolutionary approach to evaluation. Should they accept this powerful teacher evaluation tool, then, students learn to feel free to tell their teachers what they need to be successful.

Finally, in the eighth section, teachers are provided with strength-based activities that they can use with their students. We hope that with this simple explanatory Guide and its easy-to-use tools you can help your students find their way in Europe together with you!

II. A Positive Approach to

Learning Processes

As educators, too often we focus on a student’s weaknesses, what he or she needs to ‘improve’, but too little on their ‘strengths’ and ‘talents’. We often talk about their ‘needs’, ‘wants’ and ‘learning delays’. It is important to consider deficits, what students need to improve, but when deficits become the focus, the students are put on the defensive and feel excluded, especially students from a Migrant or Refugee background. Unwittingly, systemic or institutional bias expresses itself by looking at the deficits of a person, where he or she is not like ‘us’ or as good as ‘we’ are. Similarly, in low-income areas, policy decisions are often written in terms of ‘their problems’, not in terms of their ‘strengths’ and ‘opportunities’. According to the contemporary French philosopher and pedagogue, Jacques Rancières, we sometimes create inequality to endlessly chase after it. However, when we begin to focus on a student’s talents, then, we create conditions where teachers can consciously strengthen and make use of them during a given learning process. In this way, we see and approach students as a whole, rather than as an unknown other, who’s ‘lacks something’.

Different Trends in Strength-based Learning

In scientific literature, there are different trends, theories and approaches that are concerned with strength-based learning. Two of the three approaches are more limited in their scope. We will discuss these here:

WHEN WE FOCUS ON A STUDENT’S WEAKNESSES, WE ENCOURAGE A LEARNING PROCESS THAT ACCEPTS ONLY HALF OF WHO A STUDENT IS.

Strengths as areas of knowledge (Multiple intelligence theory of Howard Gardner):

Multiple or different types of intelligences are understood here as ‘strengths’.Gardner differentiates between eight (8) types of intelligences (e.g., verbal-linguistic; logical-mathematical; visual-spatial; musical; naturalistic; bodily-kinaesthetic; interpersonal and intrapersonal) that are strongly associated with educational learning capacities. The different ‘intelligences’ are not statically independent of each other and further research has shown that one strength can strongly overshadow the others.Connecting strengths to areas of learning is the most easily accessible form of education. The strengths correspond to ‘subjects’, but those strengths that not easily connected to traditional education are ignored.

Strengths as character traits (VIAA-classification of Seligman).

Seligman differentiates between six (6) virtues and classified them according to 24 strengths. He developed a test to map them out, but since the year 2000, Seligman no longer advanced research into their scientific validity. Further research, however, has shown that the six virtues can be placed under the so-called ‘Big Five’ characteristics and that his categorization of the 24 strengths under the six virtues does not really fit.

When strengths are seen as character traits, then, these are understood as fixed entities (which have the possibility to develop). This is a very deterministic vision of the human person. According to this school, strengths and talents are innate. So far, there is no scientific evidence that shows that strengths are more innate than other characteristics.

Strengths as a unique combination of abilities (Taxonomy of Bloom and Lifespan Psychology of the Dutch psychologist G. Breeuwsma).

In this school, there is a presumption that capacities can be combined with each other into higher-order skills. Heinz Werner called this the ‘orthogenetic principle’. In this vision, strengths can be developed and persons have control over the development of their strengths. In this view, a strength is combined with the concept of ‘energy’, that is to say a strength is a (unique) combination of capacities that give you energy.

In this course, we have expressly chosen this last school of thought.

STRENGTHS (TALENTS) ARE NOT INNATE: THEY CAN BE DEVELOPED.STUDENTS ARE IN CONTROL OF THEIR OWN DEVELOPMENT.

Competences and Strengths

Competences are defined as a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes. For example, ‘analysis as a competence’ combines knowledge about analytical systems, with the skills to utilize them and the attitude to apply them ‘precisely’. ‘Analysis as a strength’ is the capacity of being able to analyse something independently from a context (knowledge) or a moral position (attitude). The competence can be combined with other competences; The strength can be combined with other strengths, and can be deployed in various areas of knowledge. When someone is strongly analytical and agile and has the capacity to innovate, he or she may be a dancer, who can make spectacular choreographic moves while dancing. When someone is strongly analytical, combined with a strong capacity to observe and innovate, then perhaps he or she is someone who can create strong dance repertoires as a choreographer. Thinking in terms of competences is thinking in terms of ‘What’: what do I need to be able to know, to able to do and then to do it? Because competences also include the component of ‘attitudes’, they are far less neutral. In contrast, thinking in terms of strengths suspends judgement (for a time). For example, when someone has a strength or talent for leadership, in the positive sense, he or she can lead a class discussion, but in the negative sense, he or she is able to convince a group of young people to steal something. In this sense, the judgement about understanding strengths, or thinking in terms of them, remains the same. When thinking in terms of competences, however, a person does not have the competence of leadership when he or she steals something, because his or her attitude is not right or correct.

BY FOCUSSING OUR ATTENTION ON STRENGTHS AS SKILLS, WE SUSPEND OUR JUDGEMENT ABOUT THE STUDENT. WE ARE THEN ABLE TO LOOK FOR STRENGTHS WHETHER OR NOT THEY EXHIBIT POTENTIALLY NEGATIVE BEHAVIOUR OR ATTITUDES.

Learning in Terms of Competences or Strengths

The basic scheme of learning within a framework of competence-thinking goes back to ‘behaviourism’. The researcher-specialist-teacher determines the content of what needs to be learned, divides the content into small steps (shaping) and then evaluates whether learning has been successful. The researcher-specialist-teacher is responsible for working out the materials and the decisions about the context, content and evaluation of learning. In education, from behaviourism, we have inherited the idea of positive and negative reinforcement, which has been expanded to cognitive learning theories, but not the idea that there is an omniscient teacher who determines everything for the students. The basic scheme of strength-based learning, however, rests on the theories derived from Gestalt Psychology (Köhler). Within this framework, the researcher-teacher creates a context where it is possible to learn and where the learning objectives can be achieved. The learner determines the content of what is to be learned and evaluates or assesses him or herself. The researcher-teacher is understood to be a specialist, who creates the needed context. The learner is also seen as a specialist of her or her own learning processes. In this way, there is room for learning processes to take a different path than the traditional one. This freedom is the basic condition for the learner to be able to employ his or her strengths. A learner can only make use of his or her strengths when diverse behaviour is allowed or permitted. Competences start with the weaknesses of the learner, the so-called ‘GAP-thinking’. Strength-based learning, however, starts from the student’s strengths that can be used because the context has been set up in such a manner that their behaviours can vary.

Interestingly, in Europe, traditional educational systems are perhaps the only sectors where a ‘totalitarian regime’ is still acceptable. Thanks to the development of student advisory boards, there are of course forms of participation, but these are never concerned with the learning core, but only with side issues (e.g., drink machines, actions or events outside of the classroom, the arrangement of the playground or sometimes the workload of students). Students are rarely allowed to contribute to their own learning content, processes and feedback or evaluation.

STRENGTH-BASED LEARNING MAKES THE STUDENT A SPECIALIST OF HIS OR HER SURROUNDINGS AND LEARNING PROCESSES. THE TEACHER IS THE SPECIALIST OF THE CONTEXT. IN THIS WAY, IT IS POSSIBLE TO ACHIEVE AN EQUITABLE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENT-TEACHER.

THE ABILITY TO USE OR EXHIBIT DIFFERENT TYPES OF BEHAVIOURS IS A CONDITION TO BE ABLE TO EMPLOY ONE’S STRENGTHS.

Consequences for the Student from a Refugee or Newcomer Background

Students from a Refugee, Newcomer or Migrant background often enter into the educational system without knowing the language of instruction or they are brought up in homes where a different language is spoken. They have not followed the same educational programme as their peers, because they were not born ‘there’. Some have received an education in a different system, while others have received very little education. When the development of native children is the only norm, then, students from a Refugee, Newcomer or Migrant background automatically fall within the framework of deficit thinking, that is, in terms of their needs, shortfalls and delays. It’s for this reason that it’s important to include their strengths as an aspect of their learning process. Not only because they have strengths, but also because it allows them to be seen in their totality.

A classroom with students from a Migrant or Refugee background is in most cases already a super-diverse class. Different cultures, different languages, different visions about the world and different understandings of what it means to be human. They each bring to the classroom different experiences and even traumas, whether they are larger or smaller. It’s a bit naïve to think that they would be able to go through the same learning process as a native student, who has always lived ‘there’. However, if we include (or allow) ‘diversity’ in the learning process, then, it’s possible for the student from the Migrant or Refugee background to not only choose exercises which they feel they ‘need’, but also those that they find enjoyably challenging; that they feel that they can complete with success or are interested in completing. In this way, the intrinsic motivation of each student, regardless of whether they are natives or Newcomers, can be improved (Decy and Ryan).

The Didactics of Diversity

In order to work with the strengths of a student, we need a ‘didactics of diversity’. The lessons and assignments are presented in such a way that the student can:

-

Independently determine what the content of the lesson will be,

-

Imagine various behaviours with each assignment or exercise,

-

Take responsibility for his or her learning process by being given the space to reflect on it and to evaluate his or her progress.

When the student learns how to work in this way, then, they actually become more conscious of their own strengths and can use them positively. They are also able to use them to complement or even compensate for their weaknesses:

-

A student, who is talented in drama or theatre, might learn a language more easily in situations where he or she can improvise,

-

A student, who both easily and enjoyably learns by repetition, is perhaps better served by pointing flashcards with translations at objects in the class,

-

A student, who has strong digital skills, would perhaps learn more quickly when he or she can use a translation programme or App.

-

Teachers are responsible for creating different learning contexts where learning is made possible for a diverse classroom. Students are given the right to decide which method of learning they will use at a given time or during a particular situation or context. This is what we call the ‘didactics of diversity’.

DIVERSITY IS NOT A CONTENT OR A PRECONDITION.

DIVERSITY IS A GOAL.

Why Should ‘Diverse Behaviour’ be a Goal?

The stress theory from Hans Selye is a theory about the relationship between stress and disease, but also human behaviour. Basing himself upon the understanding of ‘stress’ from physics, Selye proposed that when an organism (i.e., people, animals and plants) is under stress, it will react to its environment with strategies that were successful in its past. To better understand how this works, we will look more closely at the behavioural aspects of Selye’s theory but not the underlying physiological processes. When someone, who is under stress, limits his or herself to behavioural strategies that were successful in the past, then, this means that some more recently learned strategies, which might be more appropriate to the situation at hand, will not be employed. If we take the phenomenon of ‘burnout’, for example, then we see that during the first phase of the illness, persons affected are unable to respond adequately to what is asked of them (with more conflicts as a result). In the next phase, they begin to protect themselves and avoid taking up any new assignments or responsibilities. In the next phase, they call in sick. And when burnout becomes very serious, patients will limit their strategies to survival strategies (eating and sleeping). A doctor or psychologist, who is specialized in ‘burnouts’, will attempt to slowly introduce or expand the number of behavioural strategies that the patient can use. Taking up new behavioural strategies (regardless of how small) can give the patient renewed energy.

If we then translate this situation to ‘working with strengths’, then, we see that persons are equipped to adequately react to their environment, when they have a larger number of behavioural strategies at their disposal. Hence, the expansion of diversity (in this case, the diversity of appropriate behaviours) should be a goal. It goes without saying, therefore, that the more behavioural strategies we know about and are able to employ in education, the greater the chance a student can connect them with his or her strengths. It follows from this that the goal of supporting students is easier to achieve when we are able to work with a more diverse class and diverse team of teachers.

We should clarify here that we understand behaviour in a very broad sense and do not limit it to ‘observable behaviour’. Thoughts, cognitions, desires and longings are also behaviours. We are concerned here about diversity in thought, in desires, in longings; hence, when educators can deal with a broader scope of diverse behaviours since they are working in a diverse environment, then, both their and their students’ skill sets will improve and expand. A common framework of values (more or less determined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) can be a checkpoint, where educators can test contexts and behaviours.

THE WALLS AROUND SCHOOLS WERE BUILT TO KEEP THOSE LEARNING INSIDE, BUT THEY ALSO KEEP THE NEIGHBOURHOOD AND LOCAL COMMUNITY OUTSIDE.

Hope

When we speak about ‘hope’ from the perspective of positive psychology, then, we distinguish between four aspects:

-

Realistic goals and expectations, or reflection and planning for your future in the long term.

-

Self-determination, or the feeling that you have control over yourself and your life.

-

Pathways, or the ability to see or to walk down different avenues to achieve your goals. This means that even when things go wrong, you don’t abandon your goals but find alternative ways to reach them.

-

Others, or working with or finding others who will include you in a hopeful future.

We must be careful not to connect the concept of hope to that of the so-called ‘American Dream’, where it is believed that everyone, regardless of context, can become successful and happy if they work hard enough.

When hope is seen as a value to work towards, then it can easily become a reproach or blame game that leads to well-meaning but potentially harmful comments like, for example:

-

You need to continue to believe in your future!

-

If you don’t believe in it yourself, then, you’ll never get there!

-

You have everything in yourself to get there, but yeah, you need to start at some point.

When working with newcomers, it’s important to make the concept of ‘hope’ concrete. What are the long-term goals that you set for yourself? Are they realistic? What are you going to do to work towards your goals (self-determination)? What paths can we plot to reach those goals and which path will you choose? Who can help you to achieve your goals? The ‘life goals planner’ is a good resource to help you answer these questions (see later).

SPEAKING WITH STUDENTS ABOUT HOPE AND HELPING THEM TO MAKE THEIR PLANS MORE CONCRETE IS A STRONG REMEDY AGAINST UNREALISTIC ‘DREAMS’

OICO-principle: Evolution in Learning and a Framework for Evaluation.

OICO is an acronym that stands for: Observation, Imitation, Creation and Originality. This principle was developed by Jacques Lecoq in École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq.

In recent times, Luc De Smet (Kleine Academie in Brussels) has further developed Lecoq’s ideas of physical theatre that reach back to the medieval concept of guilds and crafts.

When the learning paths are diverse, then, it’s not easy to evaluate each student in the same way. It’s for that reason that students must be able to see where they are positioned within the context of the larger learning trajectory or curriculum. Working with rubrics provides a solution. A rubric is a category that describes the quality and extent of a criteria. It clarifies what the different levels of expertise of a skill are and the direction the skill should develop to achieve a goal. The classification or arrangement from ‘basic’ to ‘expert’ is based on content and associated with thinking in terms of competences. The use of the OICO-principle lays out a pathway for a student to develop to master a skill.

-

Observation: I master (a part of) a skill, but not fully and learn by looking at how it is done.

-

Imitation: I master (a part of) a skill in such a way that I can imitate others or do what they are doing (e.g., complete a similar task that they have done).

-

Creation: I master (a part of) a skill in such a way that I am able to do new things (for me) or create new things with my use of it.

-

Originality: I master (a part of) a skill in such a way that I can integrate the skill with other skills and can create things that are new and original for the class.

Rubrics created according to the OICO-principle make it possible to transcend that which the students have already seen or learned in class. The students feel as though they are able to do more than what the teacher has taught them in the class. By employing the OICO-principle, students are provided with a direction for learning (towards expertise), but also their learning pathway is opened up to the possibility to use their own strengths and talents. And it’s always possible for a student to combine their newly learned skills with other strengths that keep them on the pathway to learning.

Creating a Context as Opposed to Doing Exercises

When we take learning, in terms of strengths seriously, then, we begin to realize that the learning context is just as important as the learning objectives. Competences are determined without any connection to a particular context. Strived-for competences remain the same regardless of the regional, local, architectural, material or educational surroundings in which a teacher works or student learns. When we’re too closely focussed on competences, the bulk of the responsibility for learning objectives come to rest with the teacher, and policy becomes a side issue. However, when the focus is directed towards a student’s strengths, then, in the context of learning as well as the learning objectives, become equally important.

The classical framework begins from a theory of knowledge, where the teacher is seen as the ‘specialist’. First, the theory is explained and, thereafter, the theory can be put into practice (in the best-case scenario). A math or language lesson begins first with an explanation of the theory. Afterwards, the students are required to put the theory into practice. The evaluation consists of testing ‘knowledge and skills’ based on, but never farther than, what the teacher makes him or herself.

When we teach in terms of strengths, we offer the learners both the tools and a framework. We present the materials to be learned in such a diverse way that the learners can work with them because they have a choice. Moreover, the tools and framework are presented to the class in such a way that they can even go beyond them. The tools and frameworks are ‘contexts’ where the students can move more freely about the learning environment created with the materials.

In the didactics (of diversity) the focus is on the ‘how’ instead of the ‘what’ of learning. ‘How’ does the teacher present the materials, instead of ‘what’ does the teacher present. By concentrating more on the ‘how’, the teacher ensures that step by step more diverse behaviour is acceptable.

III. The Contexts

In the context of teaching, we differentiate between time and space and in the context of the learning processes in terms of frameworks and tools. In this manual, we will first deal with the context of ‘time’ and then with the context of ‘space’. Finally, we will deal with the context of ‘frameworks and tools’. For each segment, we deal with each context according to the three areas that are essential for this Induction Course:

-

Openness, Peacefulness, Focus are the conditions that need to be in place for young people to be able to learn. When they are unable to open up to new experiences, to find peace within themselves and to sufficiently concentrate on the tasks at hand, then, learning becomes practically impossible.

-

Learning Processes or the creation of choices and an environment where diverse ways of learning become possible.

-

World or the broader context outside of the school from where the young person starts and wherein he or she will continue to live. Connection with the world outside of school ensures that learning is meaningful and can be connected to a future perspective.

After this Induction Course, we illustrate these principles with a few detailed activities for different forms of learning.

The Context ‘Time’

The context ‘time’ ensures that the student can monitor his or her own progress. The planning and the organization of the timetable and the curriculum are partially assigned to the learner. In this way, the student becomes a specialist in the timing of his or her own learning processes and is able to evaluate him or herself as well. Both the student and the teacher must remain flexible with time constraints. Next to the ability to determine long term goals, one of the most important characteristics of hope is that there are flexible pathways to reach those agreed goals, but also that there are tools available to achieve them.

To help students (and teachers) plan their pathway and reach agreed goals and objectives, we provide them with an important tool: Planners. The ‘Planners’ are more a means of communication between the student and their teacher than an instrument for evaluation. They ensure that both student and teacher find a flexible way to achieve their agreed goals together. Sometimes goals need to be adapted. Planners are one of the most important examples of tools that are used in strength-based learning. They ensure that conferences between the student and teacher are both dignified and professional. The process is deepened when the teacher also fills in the goal-planners. Not every student will stay in the induction class for an entire year. Some students are in transit to another country. In other countries or educational systems, the induction class does not last an entire school year. We numbered the months of the planners, so a teacher can adapt the planners to each student’s schedule.

LEARNING NEVER HAPPENS IN THE ABSTRACT:

IT ALWAYS HAPPENS WITHIN A CONTEXT.

Planners: Tools that allow us to make the Context of ‘Time’ More Concrete

1. The Class Planner

The Class Planner is the class timetable. In strength-based learning, we assume that a section of the timetable consists of free time to work independently. That is, blocks in the timetable are created where students can work without supervision and can choose what items they want to work and when.

4. Flow Column

In each planner, a column is foreseen each day for ‘flow’, which can also be understood as ‘energy’ (See the psychology of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi). This column doesn’t need to be filled in every day, but is an important criterion to see whether the class, student or teacher have enough positive energy. When a student, a class or a teacher is in a state of imbalance, it’s important to understand why. The connection between the moments, where positive flow and, therefore, energy is gained and moments where flow and, therefore, energy is lost, can hence be clarified. When the teacher takes the time to fill in their Planner, then, it’s possible to have an open communication between both the student and teacher. It’s recommended to request that students, who have newly arrived or are at the beginning of the school year, do this as well.

5. The Goals Planner - School

Each Newcomer is different. They have a different history, different strengths and master different skills. In the Goals Planner, the student consults with their teacher about their goals for the school year. These goals cannot be achieved during the first week of school. And the scheme doesn’t have to be filled in during the entire year. Long-term goals are important so that students are able to develop a perspective and can voice their own ambitions. Moreover, it gives them hope. The teacher’s role is to support the student in developing ambitious, yet, realistic plans. By planning goals together, it’s possible to discuss mutual expectations. These expectations can be adapted when they appear to be too ambitious, but also insufficiently ambitious.

6. The Goals Planner - Life Path

The Life Goals Planner connects the student’s identity (my life), their expectations for the future (my future) and their World View (my world) with each other. It also ensures that the student’s ambitions for life and their ambitions for school are connected. In other words, that their school goals are placed within a broader framework.

WHEN CLASSROOMS WERE CONSIDERED TO BE THE MODEL OF COMFORT AND COSINESS, THEN, HOUSES WOULD BE DECORATED LIKE CLASSROOMS

Context ‘Space’ for Openness, Peacefulness, Focus

Learning can only take place when someone is open to new experiences (Openness), has found a sense of calm within themselves (Peacefulness) and can concentrate (Focus). In strength-based learning, we see these three elements as skills. When one or more of these three conditions are not met, or when a young person has been unable to make one of the three skills his or her own, then, learning becomes burdensome.

There is no guarantee that Newcomers or Refugees can sufficiently master one or more of these three skills. But similarly, there is no guarantee that young people, who are under great stress, can use these skills adequately either. It’s therefore important that the teacher maps out to which degree a young person has sufficient openness, peacefulness and focus. Hence, in a class with Newcomers and Refugees, it’s essential to prepare activities where the student can work on his or her openness, peacefulness and focus.

Elements that can be placed within a learning space and can promote openness, peacefulness and focus:

1. When classrooms are comfortable and cosy, then, it’s much easier to support openness, peacefulness and focus.

When we’re able to create an environment where the student ‘feels at home’, then, hospitality and sociability are promoted. Elements that can assist in promoting these values could be:

-

Spaces within the classroom are decorated like a home with tables and comfy chairs, where students can sit together; including cushions that allow the students to sit on the floor.

-

Spaces where a variety of cultures are present. For example, a world map is hanging on the wall, where the students can mark their home countries; typical objects from various countries (e.g., musical instruments, items of clothing...) are present and are a part of the décor of the room, etc…

-

A place where personal objects can be displayed.

-

Plants, greenery are present and eventually, there’s a place where animals can be cared for.

2. Spaces, where classroom rituals occur, can help students to find peace and focus.

-

Racks located outside of the classroom, where students can place their shoes and pick up slippers to wear inside of the classroom.

-

A list of rules for keeping the area clean and neat. The rules are seen as a ritual when the students must do this themselves. A division of tasks that are ‘provided’ promotes peacefulness and focus less than when the division of tasks are ‘negotiated’. Moments, when the classroom is tidied up, are also moments when the students can literally come to rest and where important informal discussions can take place.

-

A shelf or cupboard where students can place a personal object or memory. When a student places an object on a shelf, he or she is ritually accepted into the classroom community. Students who permanently leave the class, take their object with them as a signal that they have left the class.

3. The presence of various cultures within the content of class projects and the materials for lessons.

-

There’s a lot that can be done or improved concerning the lack of diversity found within handbooks and lesson materials. The teacher can adjust this somewhat but isn’t able to do this completely. When own materials can be developed, then, this can be an important positive dimension.

-

The presence of and openness towards different cultures in the classroom can be strengthened by creating a class library where books from different cultures and languages are available to be used as reference materials.

-

If the classroom contains media materials and if there is an internet connection, then, it’s possible to add a bookmark in the browser. This opens up the possibility to discuss contemporary and actual issues going on in a given country or culture. Newcomers can consult this for their specific situation and even provide more nuanced or corrective information.

When spaces are arranged according to different cultures, then, this makes the spaces more vulnerable to hateful messages or actions. However, the advantage is that these attitudes and messages can be brought out into the open into the classroom and be discussed. In places where this is not possible, these negative attitudes and feelings remain ‘under the radar’ and only emerges during an open level of conflict. At this point, teachers are then forced to take a ‘restorative approach’ towards any hateful messaging or actions, which is more difficult to repair. By making various cultures visible, early on, the teacher can detect potentially negative signals before they become a problem and discuss them within the context of a strength-based approach.

Context ‘Space’ for Learning Processes

In the framework of strength-based learning, the physical space should allow for diverse learning processes. If a space is set up to only give lessons from the front, then, other forms of learning presuppose the need to move desks and chairs as an ‘exclusion to the rule’.

The space in a school is limited and it’s not always possible to accommodate all forms of learning. Nevertheless, the possibility for thought experiments and the creation of as many forms of learning as possible remains a continuous goal. Schools can, therefore, creatively play around with available common spaces, unused spaces, outdoor spaces and spaces in the neighbourhood.

When strength-based learning is applied, then, the learners are able to freely walk along diverse learning paths. This doesn’t mean, however, that everyone needs the same space at the same time. It’s only because we’ve chosen to make everyone follow the same learning path at the same time that we feel obliged to provide the same space for the entire class. Allowing diverse learning paths means that we will only need to provide a space for 4 to 8 learners. In that sense, this flexibility allows more possibilities for learning to occur.

What do we need to think about within the framework of spaces and learning processes?

-

In the classical configuration, the possibilities to allow everyone to work as well as to receive direct instruction are often combined. The question is whether these two forms of learning need to take up both the central part of the lessons as well as the largest amount of space?

-

The possibility to work together. In classrooms that are equipped to working with strength-based learning, the following configurations are given priority: large tables where students can work together in groups, where they can meet, experiment, collaborate and discover what it means to learn jointly.

-

The empty space: This type of space makes learning through movement, drama or play possible.

-

The possibility to show or discuss diverse learning paths and try them out. Next to the filling in of the Planners, learning is monitored. An overview of the process is provided by making parts of the Planners physically visible and available for review.

-

The possibility to present. This can be combined with the empty space, but also often presupposes well placed multi-media equipment.

-

The own room. Where can a learner keep his or her material when they are not working with it? We block a lot of learning opportunities because we limit the student’s access to materials to what he or she has in her backpack.

-

Availability of materials. Are there sufficient materials present, where learners can work in small groups? What material is permanently available in the class? What material does the school provide and can be borrowed? What materials do the students need to bring themselves? Finding a good balance promotes learning for everyone, including those who are not financially able to purchase materials themselves.

-

The possibility to work in spaces outside of the classroom. Does the school permit a student or a group of students to reserve workrooms themselves? Is there an overview of available space or contact information that the students can use, and are these possibilities in the neighbourhood known to the class community?

Context ‘Space’ for the World

The object of learning is not to get good grades. We learn in order to be able to eventually live an independent and happy life. When we connect school to life, then, there’s a bigger chance that learning becomes meaningful, which in turn, motivates students to learn. In the self-determination theory of Decy and Ryan, that is the precondition for ‘involvement’.

The spaces for ‘learning processes’ are concrete and physical, while spaces for the ‘world’ are rather general. They represent different physical places according to the learner’s interests, possibilities and objectives. That’s why we describe them in terms of ‘connection’. A connection can be more or less intense. Sometimes the connections are too intense and they limit the relationship with other important spaces in the world. When this happens, they then form a barrier to the development of more diverse behaviour.

In the search for connections, we once again go towards the search for strengths. Hence, the focus is not on where connections fail or are a disappointment, but where they present the possibility for and improve the chances to find diverse learning paths. For example, when we realize that some young people are not participating in free time activities, then, we might tend to think in terms of competences and see this as a weakness. We might then ask recreational organizations to ‘help’ the young person because we are focussed on ‘weaknesses’. When we start from the position of strengths and then connect these to recreational organizations, we begin to work from a more equitable basis. We translate what the student perceives he needs into what he considers to be helpful for him to accomplish that. We help the student to translate his needs into what he wants for himself. For example: “What do you need from me (teacher) for you to be able to work more quietly?”

Connections

-

Connection with the parents or the home situation: this connection is extremely important. In many countries, during primary education, the connection between parents and teachers is very strong, as most parents attend parent-teacher conferences or are at least obliged to do so. In secondary education, often, it’s only those parents of children who are doing poorly or are having problems, who come to parent-teacher conferences. Only when there is regular and deep connection with all parents can teachers clearly understand how they think about their child’s academic successes or, eventually, their estimation of the child’s weaknesses. When a relationship of trust has developed between parents and teachers, schools are in a position to ask parents to support each other and even set up alternative learning tracks, where both parents and children play a role. The responsibility for educating children is then shared. When relationships are built upon mutual trust, then, there is less room for accusations of falling short. Young people should be given a voice in the development of these relationships.

-

Connection with the home country: Sometimes, Newcomers were living in another country with another culture shortly before their arrival. There, they left behind friends, family and even enemies. This means that their relationship with their home country is ambivalent, but not necessarily negative. Does the school have contacts with persons, who can help students make a positive re-connection with their home country? Is there a possibility to follow the events evolving in their home country? Is the school able to help with the selection of reliable sources? Research but also the media have shown that young people can be easily manipulated and radicalized. When this happens, young people can become entrapped by less reliable sources. When a school, together with parents and recreational organizations work actively together, the opportunities for radicalization decrease.

-

Connection with other Migrants or Refugees from the home country: Almost every cultural or religious community from another country is somehow linked to a community in its country of origin. Especially when a city or a specific neighbourhood has a large community of persons from a particular country or culture, formal and informal contacts with the (recognized) representatives of that community are important. When we take each other’s strengths into account, then, joint projects can be set up that positively facilitate young people’s learning. The three abovementioned connections can be subsumed under the category of out-reach work. The school actively contacts others to better support the young Newcomer. In that way, his or her situation can be put into a more nuanced perspective and support can avoid mainstream prejudices.

-

Connection with the neighbourhood, free time: even though these connections might not be organized formally, often, neighbourhoods are the place where recreational activities are offered. When schools and recreational organizations are aware of each other, they can form networks that support young people when needed. For example, after school hours, schools can provide neighbourhood recreational organizations with needed spaces and areas to carry out their activities. In this way, a living community can come into being wherein the school actively participates. The gap between school and free time is then narrowed as the school and the neighbourhood become inter-dependent and benefit from each other’s strengths.

-

Connection with the neighbourhood, work: Some Newcomers feel a sense of responsibility and are compelled to financially support their families back in their home countries. When we acknowledge these realities, then, opportunities for both learning and (part-time or temporary) work can arise. The school can actively look for (temporary) work in order to help the student. Empathizing with this reality and actively helping students and their families to find a good balance can perhaps help a young person see the advantages of getting a diploma instead of prematurely leaving school. Moreover, it provides Newcomers with more opportunities to practice the new language alongside improving their cultural, social and emotional skills (SELs).

-

Connection with the neighbourhood, socio-emotional support: Some young people need extra support. They need more intensive provisions than a school can offer. When a school understands the routes a student can follow to get extra support and, eventually, access funds or subsidies, schools are able to help these students and make a positive difference in their lives.

-

Connection with the neighbourhood, neighbours: In many western European countries, a significant percentage of the adults remain at home every day. Approximately half of this percentage is pensioned, while the other half works at / or from home. There’s thus huge potential for developing projects for young people in their neighbourhoods and their neighbours. ‘Broad-based schools’, where strength-based learning is applied, have found that the development of projects in the student’s neighbourhood is an excellent way to counter both racism and bias.

The abovementioned possibilities testify to a pro-active approach. We don’t wait to speak to the neighbourhood and community leaders until young people exhibit some kind of problem. The school should actively seek contacts to better support the young person. As an old African adage says: It takes a village to raise a child. In this way, we create a community where both young people and their parents feel (more) welcome. It also opens up the possibility to receive input from a student’s community so that we can evaluate him or her in a more realistic and nuanced way so mainstream prejudices can be avoided.

Developing relationships with the neighbourhood in the function of recreation, work, but also socio-emotional support is a long-term proposition. The practices of the ‘broad-based school’ make it clear that after some time, these relationships begin to bear fruits. In this case, we achieve the result that both the neighbourhood and the school become inter-woven into, as it were, one cloth. Questions from the school to the neighbourhood or vice versa are, therefore, no longer understood as strange or unusual. Here too, we strive towards equitable relationships.

Tools that allow us to make the context of ‘space’ more concrete

1

Class Organization: students can make a map of the class and place class furniture. When the furniture can be moved, they can draw and cut out pictures of the moveable furniture and propose how they would like to arrange the class by placing the pictures on the map. The leader or teacher can impose conditions or clarify the goals of the diverse learning paths.

2

Class organization: with free software programmes that allow people to design rooms and make floor plans, students can experiment with measuring, colouring, and placing furniture. With this kind of software, they can also see the consequences of their proposals in 3D. Often the software is available in multiple languages where it becomes possible to work across different languages. An example of this kind can be found at: www.homestyler.com/int/.

3

Although most primary school classrooms have various materials on hand to use for artwork or theatre, this is not the case for most secondary school classrooms. When working with refugee and newcomer students, who do not master the native language of their host countries, art and theatre are ways that students can more easily communicate and better express themselves with their peers and teachers. For teachers in secondary education, who are interested in transitioning to a strength-based classroom, we suggest the following list of materials.

List of materials for a strength-based learning classroom.

4

With a Google account, it’s also possible to create a personal map in Google Maps via ‘My Places’. In this way, a school can create a map with relevant locations in their neighbourhood for students and their families.

With an accompanying list, for example, in Excel, a description of each location can be given and categorized. Via a hyperlink, each site can be found directly connected to Google Maps and possibly share these with students. ‘Free Time’, Work’ ‘Social-Emotional Support’ and ‘Neighbours’ can be used as permanent categories for the community map. Google ensures that everything is translated into the language of the student.

5

List of available rooms in the school that students can reserve for their own use.

6

List of available spaces that can be reserved in the neighbourhood.

7

Furnishing of spaces around the school for open-air classrooms and places to learn.

8

List of strengths (expressed in terms of skills) in diverse languages.

The ranking of the strengths is fixed so that the parents can read the strengths in their own language and the leader or teacher can determine which strengths are mentioned. Parents can choose between fifty or more strengths that apply to their child. The leader or teacher does the same based on what he or she observes in class. Normally, the student will have done this as well for his or her learning trajectory (see evaluation). An equitable dialogue can begin between all stakeholders, who are equally seen as ‘specialists’. It’s also possible to ‘read out’ the strengths via Google Translate so that parents, who are unable to read, are still able to fully participate with the help of a translator.

THE MAPPING OF A YOUNG PERSON’S STRENTHS IS NOT A JUDGEMENT BASED ON A ‘TEST’, BUT THE BEGINNING OF THE POSSIBILITY TO COMMUNICATE (ABOUT THEIR STRENGTHS)

IV. Resolving Conflicts

Strength-based learning is focussed on creating a positive class climate where conflicts and problems are recognized on time. When we implement this strategy in all classes, and not only in classes with newcomers, then, we pro-actively work on a positive school environment where students can participate in their own learning development. Classes and the school environment are set up in the function of learning. Moreover, we can connect their learning with their futures and with their neighbourhoods.

A positive learning environment has a big impact on the effectiveness of learning (Hattie), a positive learning environment is not guaranteed in all schools. Here, we provide a roadmap based on working with the context and those who are affected.

In various conflict management models, the focus is placed on the individual, who is in the wrong, with or without attention to the victim. The ‘neutral group’ is not addressed so that the incident is taken outside of its social context. Research on bullying behaviour and restorative justice makes it clear that it is important to involve the whole group and make everyone co-responsible for what has happened. When we connect this to strength-based learning, we additionally go in search of the strengths of the students who were involved in negative behaviours.

With persistent conflicts and a negative class climate, where hate speech, bullying and other problems manifest themselves, a consistent and thorough approach is needed. The administration, pedagogical team, students, their parents, and eventually the neighbourhood, are included in the process as equal partners. The responsibility for solving the conflict is placed on the class as a whole.

Step 1. Mapping out the Social Relationships and the Letter to the Parents

It’s a good idea to map out the social relationships of the entire class. It’s possible to do this with a sociogram. In the ‘tools’ section, you can find a template to construct a sociogram for two classes.

The template enables all students to express themselves in a fair way about who their friends are and who, according to them, is involved in conflicts. The students are assured from the beginning that the information will not be shared with other students or parents, except when permitted by the student.

Based on the form, we calculate two friendship scores per student:

-

How many students do I see as a friend?

-

How many students choose me as a friend?

-

The smallest circle receives a score of 1, the second smallest receives a score of 2, the third a score of 3, the fourth a score of 4, etc… You multiply the number of names per circle with the score. The lower the score, the closer friendships the student has.

In Step 1, the parents receive a letter where the problem in the class is briefly explained in general terms. In the letter, they read that the school has a plan to do something about the problem, but that they first want to allow the class to solve the problem themselves. There are two important advantages to this approach:

-

Parents, who realize that their child might be having a difficult time will be more inclined to let the teacher know about the student.

-

The parents are now informed and will probably speak to their son or daughter to understand what is happening and to what extent their children are involved.

The school should ensure that this letter is clear and understandable for all parents. It’s a necessary condition that the school takes a proactive approach with the parents, the neighborhood and local communities.

From that moment on and during each phase, the parents and eventually community leaders receive a letter about the status quo. It should be made clear what has positively changed, but also where things can be improved. Names of students should never be mentioned!

Step 2. Talk About the Conflicts and an Explanation of the Strategy and Responsibilities.

Thereafter, a de-briefing should follow where all students receive an explanation about the problems. The discussion concerns the problems from the standpoint of the students, the teachers and eventually the parents and neighbors. It’s made clear to the students that together they are responsible for solving the problem. The students, who were not involved, are also the students who knew about the conflict and did nothing about it. That’s not acceptable.

To fully encourage the class’s responsibility, they receive training in conflict solution. Others (teachers, parents and the neighborhood) are seen as sources of potential support who can be utilized later. The agreed strategy is as follows:

-

Phase 1: The class is fully responsible to solve the conflicts and negative atmosphere.

-

Phase 2: The responsibility of the class is expanded to included individual responsibilities of the students. Until the end of this phase, the parents are not informed about the behaviour of their child. If after phase 2, the problem hasn’t been resolved, then, this is done.

-

Phase 3: Parents and other teachers are brought in to be involved with individual and class.

-

Phase 4: When the conflicts have decreased and the atmosphere has improved, the class needs to agree on how they will monitor the situation to avoid reoccurring issues. In this way, the class remains responsible for signalling and recognizing problems before they become open conflicts.

Step 3. The First Discussion of Conflicts in the Class with a Restorative Circle

First, the principles of restorative circles are explained:

-

The class and the teacher sit together in a circle. Everyone is equal.

-

Everyone is allowed to speak. If someone has their turn to speak, then, everyone listens attentively and does not speak (if this is difficult, then, a ‘talking stick’ can be used. The one who is permitted to speak has control of the stick. He or she gives it to the next person who speaks).

-

Afterwards, there are different rounds of discussions:

Round 1: each student and the teacher explain in which conflict and problems they were involved in or what they saw happening to the others.

-

The teacher directs the discussion to what is observable behaviour and the moment that it happened.

-

The teacher analyses the behaviour in terms of noticeable strengths as well as a behaviour where things went wrong.

-

Only recent conflicts are discussed.

Round 2: Each student maps where he or she suffered or was (emotionally) harmed. This goes as much for perpetrators as for victims, but also bystanders.

Round 3: The perpetrators must think of ways to doubly compensate for the damage done to their victims. When a perpetrator bullies another student, then, it’s not enough to just say that they ‘won’t do it again’. For example, playing football with the victim for a week in order to let the school see that he has developed another attitude towards the victim, could be a way to make things right.

-

There is a negotiation about what constitutes the meaning of ‘double’.

-

Perpetrator and victim (and the class) need to agree on the way that things are made right.

-

The teacher repeats the suggestions in the function of the student’s strengths so that his or her strengths are best utilized.

Round 4: Activities are considered that enable the perpetrator to compensate the ‘double’ amount for the students, parents or neighbours, who were not a direct victim, but in some way suffered some kind of injury. For example, when bullying behaviour takes place in the classroom and the lessons are continually disturbed, then, the entire class and the teacher also suffer. What kind of activity will the perpetrator and the others who were involved do to make things right?

Round 5: Each activity that is agreed upon (with the perpetrators and the victims) is assigned to a neutral third party, who follows up on the activity and, where needed, provides guidance. The neutral third party remains a student.

Step 4. Beginning of Phase 1: The Students are Responsible as a Group for the Reduction of Conflict.

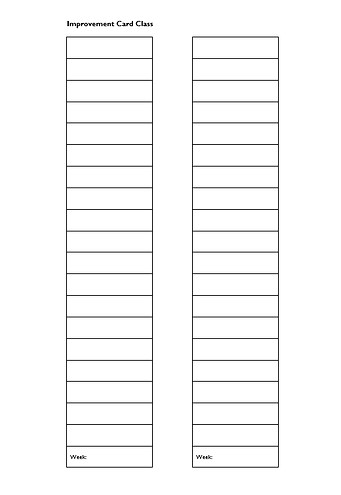

The students are told that negative behaviour needs to diminish and that positive behaviour needs to increase. It’s presumed that the entire class is responsible for this and not only the students who were involved in the conflict. Neutral students can always use their strengths to support others or mediate. In the first week, the above is discussed with the students, but no agreement is made on how negative behaviour will be reduced. We tell the students that we first want to know how serious the negative behaviour was before we intervene. This happens with the tool: ‘Class Improvement Card’.

This sheet is hung in a place where it is visible to everyone. The students get a week to make an inventory of the conflicts. Every student has the right to report a conflict or negative behaviour to the teacher. The student is allowed to explain how the conflict happened or to discuss it, but it’s not obligatory. With each report, a cell is coloured in. We begin underneath. In this way, we can determine how many conflicts happen per week.

At the end of the week, a Restorative Circle is held:

Round 1: First the actions are discussed where the offender attempted to doubly compensate for the injury or damage done. The neutral third-party student, who is responsible to follow up the action, leads the discussion. The students discuss ways they can improve on the activities that were not followed up on or were poorly executed. This point is repeated during every restorative circle until all of the activities are acceptably completed.

Round 2: The Class Improvement Card is discussed. In this round, the students can point to conflicts and map them. Some conflicts can remain anonymous, but when a student feels like a conflict or negative behaviour was not sufficiently discussed, and finds it difficult to talk about this, it is possible to address the issue after the session. The student is allowed to speak individually with the teacher, while the teacher focusses once again on observable behaviour. He or she attempts to name the strengths found in negative behaviour.

Round 3: Based on the agreed strategies, the class makes additional class agreements and rules. Thereafter, the class comes together to discuss the reduction of negative behaviour: How many fewer conflicts or negative behaviours do we want to have next week? A reduction of 25% is a good start. That makes the goal realistic and ensures that a learning process is started where diverse behaviour can be learned. When the required reduction is too extreme, the students, who are too often involved in a conflict, need to learn positive behaviour too quickly which could lead to relapses in negative behaviours.

Round 4: Each student and teacher discuss whether it is realistic for them to achieve what has been agreed. We aspire towards consensus. A second column of the ‘Class Improvement Card’ is used to measure reductions.

Step 5. Continuation of Phase 1: Follow Up and Adjustment for Fewer Conflicts and or Negative Behaviour.

Each week there is a new restorative circle where the ‘Class Improvement Card’ is discussed and agreements are adapted and revised. Here, we briefly discuss what the possible results could be.

-

The negative behaviour decreases. We just continue doing what we are doing. It’s not realistic to expect that there will no longer be conflicts. Then, you would exclude the possibility to strongly clarify something. When the class has but 2 or 3 conflicts every 2 to 3 weeks, then, you can put the ‘Improvement Card’ to the side. Every student can of course request that it be implemented again.

-

The negative behaviour decreases, except in certain situations or certain places. At first glance, the teacher sees this as positive, because generally, negative behaviour has decreased. Then we observe whether the negative behaviour is connected to particular students or specific situations. If it is connected to specific situations, then, the teacher can temporarily forbid them (e.g., when a large number of conflicts are connected to sports during free time, then, sports will be cancelled for a week). The class can ‘earn back’ sports when the teacher gives the entire class the responsibility for improvement and to show that they are capable of decreasing conflicts in other situations. Afterwards and step-by-step, sports are re-integrated into the class. For example, first sports are allowed one day per week, then, two or three… During this period, the number of conflicts that are connected to specific circumstances may not increase.

-

If the negative behaviour appears to be connected to certain students, we then go to phase 2: the responsibility of the class is now extended to the responsibility of individual students.

Step 6. Phase 2: The Responsibility of the Class is extended to the Responsibility of the Individual student.

When a particular student or students appear to be responsible for a specific aspect of the negative behaviour, and when the consequences of this behaviour are severe, then, it is immediately stopped. In principle, this concerns everything that is legally forbidden or permitted. Where and when necessary, sanctions are applied. This doesn’t mean that the perpetrator(s) need to learn other behavioural strategies in order to be able to react appropriately in the future. Action is taken at the moment that a negative behaviour manifests itself.

Next to that, when one or more student(s) exhibit(s) negative or conflictual behaviour, we use the ‘Individual Improvement Card’. Under no circumstances are the ‘Individual Improvement Cards’ discussed with the entire class. Sometimes it might be discussed in a smaller group (when, for example, it concerns reoccurring conflicts amongst the same group of students) and sometimes only with the student involved.

-

Round 1: the situations where the conflict manifests itself are mapped out. The teacher objectifies and asks the student(s) to name the strengths that were used. The negative behavioural strategies are discussed.

-

Round 2: Alternative (and positive) behavioural strategies are discussed and connected to the strengths of the student(s). Based on these observations and discussions, the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ is filled in.

YOUNG PEOPLE WHO ‘HAVE DONE NOTHING’ WRONG, ARE JUST AS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE NEGATIVE ATMOSPHERE IN THE CLASS AS THOSE WHO HAVE ‘DONE SOMETHING’ WRONG

-

Round 3: For the ‘Improvement Card’ only one (1) behaviour is chosen. This should be the behaviour that results in the most negative impact. The negative behaviour is then translated into concrete and observable behaviour that is positive. At this point, the student’s strengths must be utilized.

-

“Tom needs to improve his mood” is not a clear agreement.

-

“Toms should try to do something that makes others happy” is clear.

-

“Tom should try to leave others alone and should talk less” is an agreement that implies two strategies (i.e., leave others alone and talk less).

Together, the teacher and the student decide how often the student should employ this behaviour and when he/she does it. When it concerns employing ‘less or no behaviour’, for example, leaving the others alone, then, the day is divided into different time blocks. During each block, it’s determined whether the student was successful in refraining from the behaviour or whether he or she was able to at least reduce the behaviour.

The student chooses whether the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ can be visible in the class or not. The teacher fills in the Card in agreement with the student.

The advantage of this approach is that conflicts do not become bigger because we accentuate them, but we meet more often about the one most conflictual situation so that more alternative behavioural strategies can be developed for that kind of situation.

It’s difficult to connect punishments or rewards to the ‘Individual Improvement Card’, but that should not be a motivating factor. We always try to work with the student’s own suggestions.

Where there are more students involved in a conflict and are in the analysis of the problem, then, more students receive an ‘Improvement Card’. Sometimes we ask who would like to volunteer to participate (so that more positive behaviour is noted).

Finally, the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ can be expanded to achieve personal (learning) goals. Students can use the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ at any time to record their strengths. In this way, the Card becomes a ‘norm’ and a tool that belongs to the class culture. Hence, the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ should be used for at least half of the student’s personal (learning) goals.

Step 7. Phase 3: Parents and Other Teachers Are Included in Individual and Class Activities.

Phase 3 is announced beforehand. The students receive optimal opportunities to resolve the conflicts by themselves and before third parties are involved.

The usage of the ‘Individual Improvement Card’ makes it clear where the student should set his or her limits as well as opportunities. Third parties should not be involved when this is blocked. When we involve parents or the neighbourhood, we assume that they are there as support for the students. This can happen in three ways:

-

Young people receive an ‘Individual Improvement Card’ where behaviour outside of school is monitored.

-

Young people confer with parents, youth leaders or other important persons. The school can organize this so that the track connects to the way that the school works.

-

Parents or neighbours are asked to monitor the young person so that his or her behaviour can be better mapped. We do this when the young person is incapable of objectifying his or her behaviour. We translate this for the young person as a lack of skill and not as a ‘bad attitude’. We say the following: “It’s not yet possible for you to truthfully tell what you are doing; we’re going to work on that together.” We don’t say: “You’re lying.” (and absolutely not: “You’re a liar”).

It’s very important from this phase onward to see changes in the young person’s behaviour as an attempt to do things better, even if the behaviour is not yet or immediately constructive. A change in behaviour shows that there is a willingness to experiment with different behavioural strategies. The behaviour is objectified and translated to the young person’s not yet implemented strengths with a revised ‘Improvement Card’ as a consequence. The goal of strength-based learning is that young people develop a greater number of behavioural strategies and can positively apply them. That’s only possible when less appropriate or inadequate strategies are experimented with and not immediately punished.

Step 8. Completion of the Improvement Track and Consultations on How to Monitor.

When we base the track for improvement on strength-based learning, we try to:

-

Include the entire class in the improvement track by making use of restorative circles

-

First, give responsibility to the young people as a class to resolve their issues and then as individuals

-

Objectify their behaviour and make it concrete

-

Find strengths in their negative behaviours

-

Search for positive behavioural strategies that are based on their strengths

-

Give them time to practice the positive behavioural strategies and introduce a learning process to unlearn negative behaviours in progressive steps

-

Make this behaviour visible with the ‘Improvement Card’

-

Involve others (parents and neighbours) as a means of support

-

Never assume that a young person is bad or has a bad attitude, but instead whether he or she has learned sufficient skills to be able to take advantage of positive behaviour

-

See new or a different behaviour as a step forwards, even when the behaviour isn’t adequate to or appropriate for the situation. We are always trying to expand on different behavioural strategies.

When the class as a whole and the teachers have the feeling that the negative or conflictual behaviour has sufficiently decreased - so that the learning processes has the chance to succeed and everyone is feeling happy in the class - then the track can be halted. The class develops a plan whereby this improvement track can be discussed again. In the beginning, it’s best to do this on a weekly basis. Afterwards, discussions can be reduced to once a month. Whatever the case, it’s wise to put the issue back on the agenda after a school holiday. We often see conflicts and negative behaviours increase after these breaks as the students once again attempt to establish their social position within the group (and not because they missed ‘the structure of the school’ during the break).

The improvement track remains on the agenda until a cultural change has taken place. Not that the negative behaviour has vanished. When the point is achieved that everyone thinks: “Why are we still talking about this?”, then, the class consultations can end.

Possible Intermediate Step: Measuring Energy or Feelings of Well-Being

In the tools under the category of ‘context time’, we’ve foreseen that students can remark on what boosts or drains ‘energy’. On this basis and in general, we can see whether the students are doing well. With the tool ‘Measuring Well-being’, we can map out the students’ well-being day-by-day. At the end of the week, they fill in their top moments and their flop moments. If the discussion of the ‘Measuring Well-being Tool’ with the class is too sensitive, the teacher can discuss this individually. In other cases, the issue can be a topic of discussion in restorative circles.

WHEN YOUNG PEOPLE WHO ARE WORKING TO CHANGE THEIR NEGATIVE BEHAVIOUR, FIRST SHOW ANOTHER BEHAVIOUR, THEN, WE BEGIN TO SEE A FIRST POSITIVE CHANGE. EVEN WHEN THEIR BEHAVIOURIAL STRATEGY IS NOT YET ‘POSITIVE’

V. Mapping Strengths

Introduction

The different streams of thought about ‘strengths’ make it clear that one can map strengths in different ways. Young people who have fewer opportunities to successfully complete school benefit from looking at strengths in the broadest possible way. When we understand all of the possible strengths of a young person, there’s a better chance that we can take advantage of them. When we only make an inventory of strengths that concern school or education, we aren’t able to gain a total picture of the young person. This is especially dangerous with young newcomers. The diversity of this group is potentially so large that focussing on school strengths could amplify the dysfunctions of a particular school system.

When we map strengths, we must first take the young person’s self-image into account. What do ‘I’ consider to be ‘my’ strengths? How are my strengths connected? Which strengths boost my energy and which drain my energy? Self-image is the starting point of personal development. A young person can begin to experiment with his or her strengths using the tools that we offer in this Induction Course and with an adequate context. Experimentation clarifies:

-

Whether the young person can focus on a strength,

-

Whether he or she can use it in another situation,

-

Whether he or she needs to nuance it or call it differently,

-

Whether he or she realizes that this is not a strength and needs to search for a different strength,

The goal of this process is that the young person gains a more nuanced and objectified picture of his or her individual strengths. Mapping strengths is, therefore, the beginning of a process and not a goal in itself; nor is it a product.

There are different tools we can use to map strengths. Many of these and their underlying theories, have not been validated or are outdated. Moreover, in this Induction Course, we are unable to go over every possible tool. Nevertheless, we can propose a strategy to use not-validated tools and still gain useful information from the use of these tools.

Points of Departure

-

We start from an equitable relationship. The young person is a specialist of his or herself and has the last word. The coach or teacher is (hopefully) a specialist in strength-based learning.

-

We aspire for a broad pallet of strengths that we can translate into skills. Knowledge is therefore not a strength in itself and attitude certainly isn’t either. We translate ‘knowledge’ into ‘how’. How is knowledge used? In this way, you can arrive at a skill: search for knowledge, memorize knowledge, apply knowledge in a case study, etc… We also attempt to translate attitudes into a skill: ‘You’re messy’ becomes: “I can arrange my school materials in an orderly fashion” or “I can write legibly”.

-

We evaluate how strong our strengths are. We do that by asking for concrete examples of strengths.

-

We verify which strengths boost energy and which drain energy and continue to work with those that boost energy (we will explain this later in more detail).

-

We create a hierarchy of strengths.

Individual Action Plan

-

Ensure that you have ‘protective material’ that young people use to talk about themselves with metaphors. An example could be flashcards upon where strengths are written, or where roles, pictures of different contexts and situations are visualized. The cards with pictures especially support young people, who are coming from a different cultural context, to more easily come to a self-reflection.

-

Tell the young person that you are going to help him or her map out their strengths. Strengths are skills that boost energy.

-

Let the young person put the material into three categories: